This article first appeared on The Star and is available at this link.

IF our country’s prisons are not struggling with problems of overcrowding yet, they will do so soon enough.

Creative and constructive solutions are needed to address this problem, with an emphasis on treating imprisonment as a punishment of last resort. In other words, sentencing principles must be designed to ensure that custodial terms are no longer than strictly necessary.

Prison populations are determined by the number of offenders sentenced by the courts and the length of the incarceration imposed. The length of time which prisoners actually serve also has an impact on prison populations.

Compared to the incarceration rate of other nations around the world, ours is significantly lower than most. Currently, Malaysia’s per capita incarceration rate is very much lower than in the United States, Britain and several other nations. Almost one-quarter of prisoners worldwide are in American correctional facilities.

There are many reasons behind prison overcrowding in this country. One is the mandatory minimum sentencing laws based on the Penal Code. The intent behind these laws is to bring consistency to sentencing. However, judges in our judiciary system appear to be given wide discretion in sentencing, which in my and fellow experts’ opinion has led to some disparities in sentences for similar crimes in various towns, cities, districts and states.

Over time, those mandatory minimum laws meant that some offenders could get very long sentences for relatively minor offences or vice versa. In fact, most of the prison inmates today are non-violent drug offenders. Instead of using the sentencing to hold them accountable and treat the root of their crime, we are keeping them in prison, making their entry back into society more difficult. Drugs users who have not committed any crime should not be imprisoned. They should be treated and rehabilitated outside prison facilities. Only drug users who have committed violent and serious crimes should be imprisoned. The same applies to drug users who are habitual offenders regardless of the nature of crime.

I’m not suggesting we should go soft on crime. What I am suggesting is that we need to become smarter about how we sentence criminals and to prioritise non-incarceration in relevant cases. Although our corrections system is small when compared to other systems in the world, it has appeared to be growing in size in recent years.

Establishing sentencing guidelines is a good step towards relieving overcrowding while focusing tougher sentencing on recidivists and violent offenders. Sentencing guidelines would give judges more discretion in sentencing first-time non-violent offenders of crimes that are not serious.

Sentencing guidelines would establish rational and consistent sentencing standards that reduce disparity and ensure that the sanctions imposed for offenders are proportional to the severity of the crime committed, the offender’s criminal background, and aggravating and mitigating factors.

Sentencing should be neutral with respect to the ethnicity, nationality, gender, religion and socioeconomic status of offenders. The severity of the sanction should increase in direct proportion with the seriousness of the crime committed or the offenders’ criminal background, or both. This promotes a rational and consistent sentencing policy.

Departures from the mandatory minimum sentences established in the sentencing guidelines should be made only when substantial and compelling circumstances can be identified and articulated.

Sentencing guidelines would also allow judges to waive mandatory minimum sentences altogether for first-time, non-violent serious offenders.

It is eminent that policymakers take a close look at who is being incarcerated, why and for how long. Steps should be taken to ensure that such information are systemically analysed and regularly reported to policymakers, stakeholders in the criminal justice system and to experts in the field.

The information would invariably reveal that prisoners are disproportionately drawn from the lower socioeconomic strata group and most vulnerable segments in society. Such prisoners may be serving sentences for petty or non-violent crimes or may be awaiting trial for unacceptably lengthy periods of time. This is where sentencing guidelines and other alternative reforms to incarceration need to be implemented.

Sentencing reform is not an easy task to accomplish but it cannot be ignored. For the sake of public safety, we need to make sure that the people who should be behind bars are incarcerated accordingly. But prescribing a sort of one-size-fits-all approach to sentencing has produced the new problem of expensive prison overcrowding and the breeding of a new generation of offenders because of unwarranted imprisonment.

P. SUNDRAMOORTHY

Research team on Crime and Policing

Universiti Sains Malaysia

Past Events

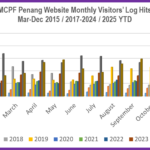

- MCPF Penang Website www.mcpfpg.org Visitors’ Log hits a Monthly Record high of 23.24k in November 2025. Cum-to-date total: 977,865 (March 2016 to November 2025)

- MCPF SPS DLC participates in Camp for Uniformed Bodies at SJK (T) Nibong Tebal

- MCPF Penang engages in Operational Meeting at SMK Mengkuang, Bukit Mertajam to follow-up on CCTV Project Proposal

- MCPF Penang Quartermaster Munusamy Muniandy does an on-site Housekeeping / Maintenance inspection of MCPF Penang Office at PDRM IPK P. Pinang

- MCPF Penang & SPS DLC participates in PDRM’s Launching Ceremony of Amanita Taman Angkat at ADTEC ATM Kepala Batas