“YOU must be honest and sincere in whatever you do. And you must work hard. There’s no substitute for hard work, you hear?” The little boy, clad in a starched white uniform, hair combed neatly to the back, listened intently, his expression solemn.

Watching his mother’s deft hands move with speed as she prepared his packed lunch for school that day in their modest kitchen, the young Lee Lam Thye knew that he’d forever carry her words with him. How could he not?

Every time she took her only son to school at the missionary-run St Michael’s Institution in Clayton Road (now Jalan S.P. Seenivasagam), Ipoh, and every time she came back to pick him up, her words echoed in his ears.

“My mum was very wise,” confides the lanky gentleman seated across from me, his kindly eyes misting slightly at the memory. His mother has since passed on but her sage advice has become ingrained in the belief system of Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Dr. Lee Lam Thye, the former Bukit Bintang member of Parliament.

Continuing, Lee, who has one elder sister but who’s passed away, says softly: “You know, even though I never had the means to further my education beyond secondary school because I came from a very poor family, and for the fact that I wasn’t smart enough to get a scholarship, I’m happy to say that I’m very much a self-made man.”

Adding, the social activist shares: “I believe in hard work, being diligent, and that if you want to do something, you have to be fully prepared to commit to it. When you can do that, I don’t see any reason why you wouldn’t be able to overcome challenges.”

Suffice it to say, his record speaks for itself. Gentle and courteous, Lee’s well loved by Malaysians and held in the highest esteem by all strata of society — from royalty to the man on the road — for his dedication and commitment to everything he touches.

For more than 21 years, Lee, who was also a member of the Advisory Board of the Kuala Lumpur City Hall for 16 years, served the people tirelessly and relentlessly. The Bukit Bintang constituency was his first home, and the Kuala Lumpur City Hall, his second.

Today, at the age of 76, the flames continue to burn bright — brighter than the world just beyond the large windows of this empty restaurant at the Royal Selangor Golf Club, Kuala Lumpur, overlooking a rolling golf course, where Lee, who actually lives in Kampung Pandan, prefers to meet friends and reporters seeking his thoughts (“It’s better than coming to my office at home where it’s just so messy with books and files,” he’d confessed).

The hitherto sunny afternoon has turned slightly downcast as the threat of impending rain looms, with the clouds continuing on their regal march across the canvas of blue. Tell me about your new book, Tan Sri, I say to him, dragging my eyes away from the view of golfers engrossed in their midday game and reaching for my copy of Call Lee Lam Thye! Recalling a Lifetime of Service from my bag.

His beam is wide as the dignified six-footer, whose final handicap before retiring from the game (golf) was 18, makes himself comfortable on the chair, carefully plumping up his cushion, which has become his constant companion ever since being diagnosed with cervical spondylosis (age-related degeneration of the bones and disks in the neck) and lumbar spondylosis (degeneration of the vertebrae and disks of the lower back).

A RESPONSIBILITY

Taking a quick sip of his warm water before beginning his story, Lee shares: “Actually, the idea to do the book came to me more than five years ago. I felt I needed to put things on record, not just for my benefit but also for my children and the young generation.”

Lee, born on Dec 30, 1946 in the small town of Menglembu, Perak, confides that he wants his book to inspire people. And that it’s not political in any way. “I’m using myself as an example,” he says, simply.

He adds: “At the age of 23, I already had in me that ‘voluntary’ spirit and I was serving the people. I was young and energetic and worked 16 to 17 hours a day. If there was a fire in the wee hours of the morning and I received a call from the fire department, I’d rush to the scene. There was no such thing as inertia in my vocabulary.”

He fervently aspires to inspire young Malaysians to do more for their beloved country. “I always believe that we can’t just depend on the government. Even if it’s the best government that you can get,” says Lee, before adding emphatically: “You can’t. In the end, you still have to depend on the people. We have a civic responsibility and duty to the country and each other.”

A gentle smile crosses his face when Lee confides that it always warms his heart whenever he sees or reads about Malaysians of all races, regardless of class or creed, rallying together in the face of adversity.

“The Covid-19 pandemic, the flooding, and disasters… see how Malaysians are able to unite when it really matters,” he states, continuing: “We need to encourage more people to have this selfless and voluntary spirit. Don’t do things only when there’s a carrot dangled in front of you. If my book can inspire even 10 per cent of the population to do something, I’d be a very happy man.”

I mention to the soft-spoken former politician how taken I am by the cover art on his book drawn by another Malaysian icon, cartoonist Datuk Mohammad Nor Mohammad Khalid, popularly known as Lat. To my surprise, Lee suddenly looks wistful. His eyes travel slowly to the window and his gaze turns thoughtful.

Recalls Lee: “Actually, that cartoon by Lat appeared in the New Straits Times back in October 1990. I’d already announced that I wasn’t going to stand for elections due to some political problems with the party. The picture showed a squatter house located by the side of a river. It was monsoon time and the house was about to collapse.”

Continuing his story, he adds: “The owner, an old man, had rushed out (of the house) and with his two bare hands was trying to hold on to that portion (of the house) that hadn’t collapsed yet. At that very moment, his son came home from school. When the man saw him, he shouted, ‘Quick, call Lee Lam Thye!’ And the son replied, ‘Papa, he has retired.'”

Again, that wistful smile when Lee confides: “When this cartoon was published, I remember looking at it again and again. And the more I looked at it, tears started to roll down. Why? Because I couldn’t help thinking about all the years of hard work that I’d put in to look after the people in my constituency of Bukit Bintang.”

Lat’s cartoon, he says, speaks volumes. “In those years, in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, whenever there was a problem in Kuala Lumpur, the people always thought of Lee Lam Thye. It’s this kind of spirit that I continue to bring to the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that I work with now. I’ve said it time and time again: I may have retired from politics, but I’ve never retired from the nation or the community. I still serve, albeit in a different capacity.”

FOREVER IN SERVICE

There’s not much difference to his days today compared with when he was still in politics, admits Lee, smiling sheepishly. “Back then, I’d be busy attending Parliament, taking up people’s grievances and presenting their problems to the relevant authorities. It was a full-time job, which meant I couldn’t go and work elsewhere because I had to concentrate all my time and resources to what I was doing. Even on weekends, I was busy. I’d turun padang (go down to the ground) and meet people, organise gotong royong etc.”

After retiring from politics in 1990, he got heavily involved with various non-governmental organisations (NGO) groups. The quieter, less hectic public life that his family had eagerly anticipated when the patriarch left the political arena was never meant to be, hardly surprising given his personality and drive.

For a while, Lee continued to maintain his social service centre in Jalan Tun Razak, Kuala Lumpur, which offered assistance and advisory service to the public despite not being an elected representative of the people anymore.

Says the former boy scout: “At one point, I was involved with about 12 NGOs, mostly serving as a volunteer. Thankfully, I had sources of income — one was the pension I got from parliament and the state assembly. I was also appointed as chairman of two foundations. I did a lot of work with the SP Setia Foundation, and later, the ECO World Foundation, both of whom paid me a monthly allowance.”

He took a particular interest in the committees. “I’d attend their meetings and listen to what they had to say,” shares Lee, adding: “And if they wanted my advice, I’d offer it. When there were times that I needed to draw their attention to certain issues, I’d do so. This ‘work’ kept me pretty occupied.”

From animal welfare to crime prevention, mental health and organ donation, Lee continued to be an active proponent of various causes through his work in many associations, NGOs, commissions and foundations.

Chuckling, the father of two sons admits that it’s fortunate his family is — and has been — very understanding. “They don’t interfere,” he shares, tone laced with gratitude. “They say, ‘just do whatever you like!’ I must really give credit to my wife. There have been times when she’s left all on her own in the house with just the maid, looking after all my pets. I’d be out the whole day. But she has never once complained.”

BIG DREAMS

Rewinding back the years, I ask Lee, the son of blacksmith Lee Kan, who eked out a living at his small iron foundry, and whose mother, Chooi Foong Keng held court at home, nurturing and guiding the young Lee and his elder sister, why he ever got himself into politics.

He nods, as if it’s a question he’s been asked many times before. “It all started from my school days. Back then, I was a voracious reader and read the newspapers a lot. When I was in Form 3, I used to buy a newspaper called the Eastern Sun. My teachers had stressed upon us to read if we wanted to improve our English. And so, I started reading the newspaper daily. The politics page intrigued me most.”

A political figure whom he admired and whose career he ardently followed back then was former Singapore Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who, along with his colleagues, had founded the People’s Action Party (PAP) in November 1954.

Smiling at the recollection, Lee, who confesses to having little time to read books but loves poring over short articles written by New Straits Times’ columnists, continues: “I remember thinking that one day I should become a politician so that I’d be able to use my political office not to enrich or benefit myself, but as a vehicle for me to serve the people. And that’s exactly what I did for 21 years, starting as a state assembly representative in 1969 to 1990.”

A brief pause ensues when I ask Lee which superpower does he wish he has, if given the choice. His brows furrow as he contemplates the question. Then nodding thoughtfully, he replies: “The power to bring about more change. Looking around today, it depresses me to see the problems that have beset our country. The rising cost of living and its effects on the B40 group, especially, saddens me.”

Continuing, he says emphatically: “I understand the meaning of poverty. When I was growing up, it was bad enough but now it’s even worse. We used to live in a wooden house, situated on a Temporary Occupation Licence (TOL) land in Menglembu. It was quite a big house and we had a fairly big piece of land. My mum and dad planted a lot of fruit trees. We had rambutan, ciku (sapodilla), mangoes, pineapple, mangosteen — it was just like an orchard.”

At least back then, he points out, they had fruit trees to supplement the family’s income. Shares Lee: “During the school holidays, I’d climb the trees and pluck the fruits to sell to the traders at the market. I cycled from my home to the market, which took 20 minutes. I was in Form 1. But think of those people living in the low-cost housing today — the B40 group, for example. They’ve nowhere to go and no place to plant anything.”

A pregnant pause ensues as we both take in the enormity of what had been said. Suddenly, Lee pipes up: “Did I tell you I’m planting vegetables at my semi-detached house in Taman Maluri now? I have my buku hijau!”

Huh? He’s swift to catch my look of confusion — both at the sudden change of mood AND topic. Lee smiles and proceeds to patiently explain: “The Buku Hijau programme was started by Tun Abdul Razak Hussein in 1974 during his time as the prime minister, which encouraged the people to plant things if they had any green space at their home.”

Eyes dancing with enthusiasm, he shares that he’s planted a papaya tree and a small guava tree, which have borne fruits. “I’ve also planted vegetables with my maid’s help. The first thing I do when I reach home is to check on my vegetable plot. It gives me joy to see the papaya fruit growing bigger. Alhamdulillah, it’s very therapeutic. I guess for someone who doesn’t find it easy to relax, this is how I relax!”

Leaning back into his chair, he says softly: “I have no plans to make a comeback in politics or join other parties. I’ve retired. But if there’s one thing I’d love to do if I had the power is to set up a foundation. I dream about this all the time but I don’t know how I can do it, especially with my age now and the current situation.”

Lee elaborates it’s his fervent wish to be able to set up something like a Yayasan Lee Lam Thye. Inhaling deeply, he continues: “I want to have the power to set up my foundation so I can employ people to work with me, and in turn help a lot more people — much more than what I’ve been able to do in the past and what I’m doing today. But with no funds, I guess it’ll always be just a dream.”

Do you have other aspirations, I couldn’t help blurting out, intent on lifting the blanket of gloom that’s threatening to descend.

The smile returns. “I’d like to do more for my wife,” replies Lee, again that sheepish smile crossing his face. “I’ve neglected her for far too long. I really hope I can take her for a holiday — without work! She’s made many sacrifices. My wife needs care and attention too now. For all my achievements, I’ve to say that she’s been the biggest contributor to them. She and my children.”

Lee has two sons — the younger one is an actuary in the UK, working in the biggest insurance bank there. “I don’t think he’s coming back,” he confides, adding that his elder son, meanwhile, is in the country working in the private sector.

A small chuckle escapes his lips when he shares: “There have been times when people have asked me why I don’t get my son involved in politics — like a chip of the old block etc. But he has absolutely no interest in politics whatsoever. I guess we’re just a dying breed!”

MERDEKA AND BEING MALAYSIAN

With Malaysia’s 65th Independence Day just mere days away, Lee has quietly been preparing for it. Every year without fail, he’d bring out his treasured Jalur Gemilang flag and put it up in front of his house.

His voice low, he says: “I look around my housing estate and other housing estates, I don’t see many people flying the flag anymore. Maybe they think, well, I don’t have to fly the flag just to show my loyalty. But in my case, it’s different. The Jalur Gemilang is a sense of pride for me.”

Continuing, Lee adds: “I want people to know that this is our Merdeka Day and we should show our respect and love for this very important day. I mean, you don’t have to fly the flag every day. Foremost on my mind are the issues of unity, nationalism, and patriotism. I fly the flag because I want to show that I’m patriotic. I’m not trying to bodek anyone, let alone the government. The government and the flag aren’t connected.”

Malaysians, he continues, should not equate the flag with the government. “Does it mean just because you don’t love the government that you should fall out of love with the nation too? I really want more Malaysians to understand what independence really means. We’re masters of our own destiny.”

Our diversity is our strength, believes Lee. And it should never be politicised. “It’s not a weakness,” he reiterates, emphatically, adding: “We can use it to mobilise and unite all the different races to help one another to build a strong nation. Our diversity should be celebrated.”

Talking about race will always be controversial. Lee believes that after 65 years of independence, we’ve come to a stage where we should be able to first recognise ourselves as Malaysians, irrespective of our ethnic background. “If you want to talk about race, well, we only really have one race — the human race,” he says, simply.

His gaze drifting to the slopes beyond the glass windows again, the self-confessed moderate concludes softly: “It’s sad that politics is dividing this country — the politics of race. It’s not the people. How to overcome this is beyond me. Except that I want to set myself as a true Malaysian. Before I tell others what they should do, I set an example first. And this is what I’ve been doing all this while. The Malaysian flag is the flag that I fly. It’s my flag. And it’s the nation’s flag.”

Call Lee Lam Thye!

By: Sofea Chok Suat Ling and P. Selvarani

Published by: Nightingale Printing Sdn Bhd

Pages: 312

Available in Kinokuniya and on Shopee and Lazada. Or email [email protected].

English version (hardcover) – RM70. English version (softcover) – RM50.

Chinese version (hardcover) – RM75. Chinese version (softcover) – RM60.

This article first appeared on New Straits Times.

Past Events

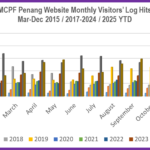

- MCPF Penang Website www.mcpfpg.org Visitors’ Log hits a Monthly Record high of 23.24k in November 2025. Cum-to-date total: 977,865 (March 2016 to November 2025)

- MCPF SPS DLC participates in Camp for Uniformed Bodies at SJK (T) Nibong Tebal

- MCPF Penang engages in Operational Meeting at SMK Mengkuang, Bukit Mertajam to follow-up on CCTV Project Proposal

- MCPF Penang Quartermaster Munusamy Muniandy does an on-site Housekeeping / Maintenance inspection of MCPF Penang Office at PDRM IPK P. Pinang

- MCPF Penang & SPS DLC participates in PDRM’s Launching Ceremony of Amanita Taman Angkat at ADTEC ATM Kepala Batas