This article first appeared on FMT by Robin Augustin on May 6, 2017. Image above is sourced from FMT.

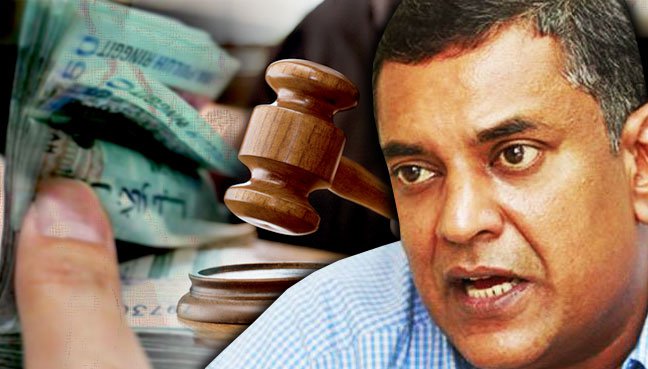

PETALING JAYA: A criminologist has voiced concern that the introduction of the Islamic law of diyat may reduce the deterrent effect of conventional punishments for violent crimes like murder.

Speaking to FMT, P Sundramoorthy of Universiti Sains Malaysia called for a thorough study of the matter.

The Regent of Pahang recently announced that the Pahang Pardons Board was planning to adopt diyat as an alternative to the granting of pardons to convicts awaiting the death sentence. Diyat is the financial compensation paid to the victims or their heirs in cases of murder, physical harm and damage to property.

Sundramoorthy said: “Among scholars and experts in Islamic law, there is continuous active debate on whether the concept of diyat, as a form of punishment, is viewed as retributive, retaliatory or compensatory in nature.

“Diyat serves its purpose effectively in countries where shariah laws are implemented. It has it strengths but can also be abused like all other laws if the intention of the presiding judge is malicious or biased.”

Sundramoorty said criminologists viewed punishment as a means of deterring an offender from repeating an offence and others from committing similar offences.

In the case of Malaysia, which has inherited the British philosophy of crime and punishment, the justice system incorporates the major elements of incapacitation, retribution, restitution and rehabilitation.

Sundramoorthy said two important questions needed to be addressed with regard to the introduction of diyat. “First, to what extent will diyat discourage serious crimes like murder and other violent crimes? Second, to what extent will diyat encourage acts of intentional killings or serious injuries?”

He said these questions arose because with diyat, there wouldn’t necessarily be one eventuality for those who intentionally killed others.

He said it would be prudent for the authorities to thoroughly study the matter, weighing advantages against disadvantages and considering whether justice would be served in the eyes of the families of victims of murder and other aggressive crimes.

Amnesty International Malaysia has voiced some concerns over the plan to adopt diyat, saying it feared the consequences of giving private individuals the power to decide on a person’s life.

It said the poor, for instance, would be left at a disadvantage because they might not have enough money for compensation.

Under Article 42 of the Federal Constitution, the power to pardon convicts lies solely in the hands of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong or the sultan of a state.

Malaysia is one of 30 countries that still enforces the death penalty. It is applicable to murder, drug trafficking, kidnapping, waging war and firearms offences.

Prison Department statistics show there are almost 800 prisoners, both Malaysians and foreigners, currently on death row for drug trafficking offences.

Critics of capital punishment argue that there is no evidence to suggest that the death penalty reduces crime.

Past Events

- MCPF Penang congratulates PDRM – RMP on their 218th Police Day Celebrations

- MCPF 32nd Annual General Meeting at DoubleTree by Hilton Putrajaya Lakeside

- MCPF EXCO Meeting No. 1 (2025/2026) at DoubleTree by Hilton Putrajaya Lakeside

- MCPF Penang Chairman Dato’ Ong Poh Eng holds a dialogue session on MCPF Penang fund raising approaches

- MCPF Penang Chairman Dato’ Ong Poh Eng is recognized by Bukit Aman’s Director of Narcotics Crime Investigation Department